TL;DR

A good diet for osteoporosis centers on calcium-rich foods (1,000-1,200 mg daily), vitamin D (800-1,000 IU), adequate protein (1-1.2 g per kg body weight), and bone-supporting nutrients like magnesium, vitamin K2, and omega-3 fatty acids. The best approach combines dairy or fortified alternatives, leafy greens, fatty fish, nuts, seeds, and lean proteins while limiting excess sodium, caffeine, and alcohol. Supplements fill gaps when diet falls short, but whole foods provide superior absorption and additional nutrients. This guide brings together the key nutrition principles needed to support and maintain bone health.

Key Takeaways:

✓ Calcium and vitamin D work together. You need both.

✓ Protein is essential for bone matrix, not just calcium.

✓ Gut health affects nutrient absorption.

✓ Food sources beat supplements when possible.

✓ What you avoid matters as much as what you eat.

Table of Contents

- Nutrition as the Foundation of Bone Health

- Essential Nutrients for Strong Bones

- Best Foods for Bone Health

- What to Limit or Avoid

- Special Considerations

- Supplements: When and What to Take

- Meal Planning Made Simple

- Nutrition and Vibration Therapy Together

Nutrition as the Foundation of Bone Health

Your bones are living tissue. They are constantly breaking down and rebuilding, even in adulthood. This ongoing cycle, known as bone remodelling, depends on a steady supply of specific nutrients. Without them, bone density declines, no matter what other therapies are in place.

A good diet for osteoporosis focuses on providing the nutrients bones need to maintain density, support repair, and reduce fracture risk over time.

Bone-supporting nutrients work together rather than in isolation. Calcium provides structure. Vitamin D helps the body absorb and use that calcium effectively. Protein forms the framework that minerals attach to. Magnesium, vitamin K2, and other trace nutrients support the chemical processes that allow bone formation to occur.

Diet plays an active role in bone maintenance. People who consistently consume enough of these nutrients tend to preserve bone density longer and experience fewer fractures with age than those who do not. Nutrition does not simply slow loss; it supports ongoing repair.

The problem is intake. Many adults fall short, especially as they get older. Calcium intake often drops after midlife, and vitamin D deficiency is common, particularly in northern climates and during winter months.

A bone-focused diet is not complicated, but it does require intention. Understanding which nutrients matter most, where to get them, and how they work together creates a foundation that supports every other aspect of bone health.

Essential Nutrients for Strong Bones

Strong bones depend on a small group of core nutrients that work together to maintain structure, support repair, and respond to physical stress. Calcium, vitamin D, and protein form the foundation. Other nutrients support this system by improving absorption, regulation, and balance over time.

Calcium

Calcium provides the mineral structure of bone. Nearly all of the calcium in your body is stored in your skeleton, and your body will draw from those reserves to keep blood calcium levels stable. When intake falls short, bone tissue gradually weakens.

Daily needs increase with age. Most women over 50 and men over 70 require about 1,200 mg per day, while men between 50 and 70 need closer to 1,000 mg.

Food sources vary in how well they are absorbed, but several stand out for both availability and reliability. Dairy products such as plain yogurt and cheese provide concentrated calcium that is easy for the body to use. Fortified plant milks and calcium-set tofu can offer comparable amounts when properly fortified. Small fish eaten with the bones, such as sardines, and cooked leafy greens like collard greens also contribute meaningful amounts.

Calcium absorption is limited to roughly 500 mg at a time, so spreading intake across meals works better than consuming it all at once. Vitamin D status strongly influences how much calcium your body can actually use, which makes these two nutrients inseparable in practice.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D allows calcium to move from the digestive tract into the bloodstream and from the bloodstream into bone tissue. Without enough vitamin D, even a calcium-rich diet is less effective.

Recommended intake increases with age. Adults over 50 generally need between 600 and 1,000 IU daily, with higher needs common in older adults and those with limited sun exposure.

Fatty fish such as salmon and sardines provide the highest natural food sources. Fortified milk, plant milks, and cereals contribute smaller amounts. Egg yolks add modest support.

Sun exposure triggers vitamin D production in the skin, but geography, season, skin tone, age, and sunscreen use all affect how much is produced. In Canada, vitamin D supplementation is common, particularly during fall and winter.

Protein

Bone is built on a protein framework, primarily collagen, that holds minerals in place. Adequate protein intake supports bone formation, preserves muscle mass, and helps protect against falls, which are a major fracture risk factor.

For most adults, a minimum intake of 0.8 g per kg of body weight meets basic needs. For bone health, many people benefit from closer to 1.0 to 1.2 g per kg daily. A person weighing 68 kg, or about 150 lb, typically needs between 68 and 82 g per day.

Both animal and plant proteins contribute effectively. Poultry, fish, eggs, dairy, legumes, tofu, and lentils all play a role. Animal proteins tend to be more protein dense, while plant sources often provide additional minerals such as magnesium and potassium. A mixed approach works well for most people.

Magnesium and Other Supporting Nutrients

Once calcium, vitamin D, and protein are in place, supporting nutrients help regulate how bone tissue forms and adapts.

Magnesium plays a regulatory role by helping activate vitamin D and control calcium transport. Many adults consume less than recommended amounts, particularly those who eat few nuts, legumes, or leafy greens. Almonds, beans, spinach, edamame, and dark chocolate are practical food sources.

Vitamin K2 helps direct calcium into bone tissue and away from arteries. It appears in small amounts in eggs, cheese, and fermented foods such as natto and sauerkraut. Leafy greens supply vitamin K1, which the body can partially convert to K2.

Omega-3 fatty acids support bone health by reducing chronic inflammation, which is linked to increased bone breakdown. Fatty fish such as salmon, sardines, anchovies, and mackerel provide EPA and DHA directly. Plant sources like flaxseeds and walnuts contain ALA, which the body converts at lower rates.

Together, these nutrients create the internal environment bones need to maintain strength and adapt over time. Calcium, vitamin D, and protein do the heavy lifting. Supporting nutrients fine-tune the process and help ensure that the system works efficiently rather than under strain.

Best Foods for Bone Health

Bone-supportive eating works best when a few food categories show up consistently. These foods deliver calcium, protein, and supporting nutrients in forms your body can use day after day.

Dairy and Calcium-Rich Alternatives

Dairy remains one of the most efficient ways to meet calcium needs, especially when paired with adequate protein and vitamin D.

Reliable options include plain Greek yogurt, milk, and hard cheeses such as cheddar or parmesan. Cottage cheese offers higher protein with moderate calcium.

For lactose intolerance, these are often well tolerated:

- Lactose-free milk

- Aged hard cheeses

- Yogurt with live cultures

Non-dairy alternatives can also contribute when fortified. Fortified soy milk offers the closest protein match to dairy. Fortified almond, oat, or cashew milks; calcium-set tofu; and fortified plant-based yogurts can support intake when labels confirm adequate calcium and added vitamin D.

Aim for products that provide at least 300 mg of calcium per serving.

Leafy Greens and Vegetables

Dark leafy greens contribute minerals that support bone maintenance and complement calcium-rich foods.

Collard greens, turnip greens, kale, bok choy, and broccoli are practical choices. Greens higher in oxalates, such as spinach, Swiss chard, and beet greens, still offer nutritional value but are less effective as calcium sources.

Cooking greens improves mineral availability and portion tolerance.

Protein Sources

Including a protein source at each meal supports bone structure and helps maintain muscle mass.

Fish and seafood such as salmon, sardines, and mackerel provide added value. Canned fish eaten with the bones contributes additional calcium.

Poultry, lean meats, and eggs offer concentrated protein. Plant-based options, including lentils, beans, tofu, tempeh, edamame, and quinoa, contribute protein along with complementary minerals.

A simple pattern works well for most people:

- Protein-centred breakfast

- Protein-anchored lunch

- Protein-forward dinner

- Protein-containing snacks

Nuts and Seeds

Nuts and seeds offer compact sources of minerals and healthy fats.

Almonds, walnuts, cashews, Brazil nuts, chia seeds, sesame seeds, ground flaxseeds, and pumpkin seeds are all useful additions. Nut and seed butters provide the same nutrients in a more concentrated form.

Small daily amounts add up.

Bone Broth and Collagen

Bone broth provides minerals and collagen derived from bones during long simmering. It can be used as a beverage, soup base, or cooking liquid for grains.

Collagen supplements may offer additional support, particularly in postmenopausal women. Whole food sources remain the priority, with supplements filling gaps when needed.

What to Limit or Avoid

Bone health is supported not only by what you include but also by what you keep in check. These factors do not need to be eliminated entirely, but consistently high intake can work against bone maintenance over time.

Excess Sodium

High sodium intake increases calcium loss through urine. Over time, this can make it harder to maintain adequate calcium balance, even when intake appears sufficient.

For most adults, staying under 2,300 mg of sodium per day is a reasonable upper limit. For bone health, many people benefit from keeping intake closer to 1,500 to 2,000 mg daily.

Sodium is most concentrated in processed and restaurant foods, including:

- Processed meats such as deli meat, bacon, and sausage

- Canned soups and broths

- Takeout and restaurant meals

- Frozen dinners

- Condiments like soy sauce, ketchup, and salad dressings

- Packaged snacks

Cooking at home more often and choosing low-sodium or no-salt-added products helps keep intake in a supportive range without sacrificing flavour.

Caffeine

Moderate caffeine intake does not appear to harm bone health. Issues tend to arise only with consistently high consumption.

Most people tolerate 200 to 300 mg of caffeine daily without concern. Intake above 400 mg may interfere with calcium balance, particularly if overall calcium intake is low.

Common sources include coffee, espresso, tea, and cola. A practical way to reduce impact is to consume caffeine alongside calcium-rich foods. Adding milk or fortified plant milk to coffee helps offset small calcium losses.

Alcohol

Regular heavy alcohol intake interferes with calcium absorption, disrupts vitamin D metabolism, and impairs bone-forming cells. Over time, this significantly increases fracture risk.

For bone health, intake is best kept within these limits:

- No more than one drink per day for women

- No more than two drinks per day for men

Including alcohol-free days during the week further reduces cumulative effects.

If you have osteopenia or osteoporosis, limiting alcohol supports better outcomes and complements other treatments.

Excess Vitamin A from Supplements

High doses of preformed vitamin A, also known as retinol, can interfere with vitamin D activity and accelerate bone breakdown. This concern applies primarily to supplements rather than food.

Total intake from supplements should not exceed 3,000 mcg, or 10,000 IU, daily. Foods rich in beta carotene do not carry the same risk, as the body converts only what it needs into active vitamin A.

Extremely High Protein Intake

Protein supports bone structure when calcium intake is adequate. Concerns about protein causing calcium loss apply mainly to extreme intakes combined with low calcium consumption.

For most people, protein intake up to 1.5 g per kg of body weight supports bone health and does not increase fracture risk. Adequate calcium remains the key factor that keeps protein working in your favour.

Special Considerations

Nutrition recommendations apply broadly, but certain situations affect how well nutrients are absorbed, used, or retained. These factors do not change the fundamentals of a bone-healthy diet, but they can influence how much attention and consistency are required.

Gut Health and Nutrient Absorption

The digestive system plays a direct role in bone health by determining how effectively calcium, vitamin D, and other nutrients are absorbed. Even with adequate intake, poor absorption can limit results.

Conditions that commonly interfere with absorption include celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, lactose intolerance, and low stomach acid, which becomes more common with age. Each of these can reduce calcium uptake either directly or through dietary restriction.

Supporting gut health helps improve nutrient availability. Fermented foods such as yogurt, kefir, and sauerkraut support microbial balance. Prebiotic fibres found in foods like onions, garlic, asparagus, and bananas help feed beneficial bacteria. When digestive conditions are present, working with a healthcare provider or dietitian ensures nutrient needs are met without triggering symptoms.

For people with celiac disease, strict gluten avoidance is essential to allow intestinal healing. Once the gut lining recovers, absorption of calcium and vitamin D improves significantly, making dietary consistency especially important.

Medication Interactions

Several commonly prescribed medications influence bone density or interfere with nutrient absorption. Corticosteroids, long-term use of proton pump inhibitors, some antidepressants, and certain diabetes medications are all associated with increased bone loss.

Other medications affect how nutrients are taken up. Bisphosphonates require an empty stomach to be absorbed properly. Calcium supplements can interfere with thyroid medications and some antibiotics when taken too closely together.

If you take medications that affect bone health or absorption, monitoring and timing matter. Any adjustments to supplements or treatment plans should be discussed with a healthcare provider rather than managed independently.

Body Weight and Bone Health

Body weight influences bone density through both nutrition and mechanical load.

Being significantly underweight increases osteoporosis risk due to lower nutrient intake, hormonal changes, and reduced stress on bones. In these cases, prioritizing nutrient-dense foods, adequate protein, and sufficient calories supports both weight restoration and bone health.

Rapid or aggressive weight loss can also accelerate bone loss. When weight reduction is necessary, gradual changes paired with adequate protein, calcium, vitamin D, and weight-bearing activity help minimize negative effects.

Moderate body weight provides some protective stimulus to bones, but overall health still matters more than weight alone. Consistent nutrient intake remains the priority at any size.

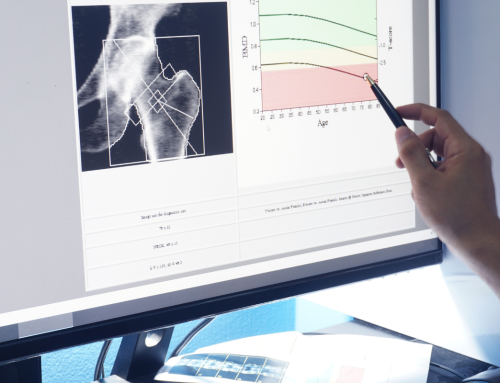

Osteopenia and Osteoporosis

The nutritional approach for osteopenia and osteoporosis is largely the same. The difference lies in urgency rather than strategy.

With osteopenia, nutrition and lifestyle changes focus on stabilization and prevention. This stage offers an opportunity to slow or stop further bone loss through consistent habits.

With osteoporosis, nutrition becomes a critical part of a broader treatment plan. While diet alone may not reverse advanced bone loss, every improvement supports fracture risk reduction and treatment effectiveness.

In both cases, long-term consistency matters more than short-term changes.

Supplements: When and What to Take

Food should cover most nutrient needs whenever possible. Supplements are useful when intake falls short, absorption is impaired, or specific deficiencies are present. They work best when filling gaps, not when replacing food.

Supplementation is often appropriate for people who cannot meet calcium needs through food, have limited sun exposure, take medications that interfere with absorption, or have confirmed deficiencies based on blood testing.

Calcium Supplements

Calcium supplements help fill gaps when dietary intake is consistently low. The form and timing matter.

Calcium carbonate is the most concentrated and least expensive option, but it requires stomach acid for absorption and is best taken with meals. Some people experience digestive discomfort.

Calcium citrate is absorbed well with or without food and is often better tolerated, particularly for those who use acid-reducing medications. The tradeoff is lower elemental calcium per pill, which means larger or more frequent doses.

The body absorbs calcium most efficiently in doses of 500 mg or less. If supplementation exceeds that amount, splitting doses across the day improves absorption. Total calcium intake from food and supplements combined should generally remain below 2,000 to 2,500 mg daily.

Calcium supplements should be taken separately from iron supplements, thyroid medications, and certain antibiotics to avoid interference with absorption.

Vitamin D Supplements

Vitamin D status strongly influences how well calcium is used.

Vitamin D3 is the preferred form for most people because it raises and maintains blood levels more effectively. It is derived from lanolin or lichen and is best absorbed when taken with a meal that includes fat.

Vitamin D2 is plant-derived and sometimes prescribed in higher doses, but it is less effective for long-term maintenance.

Many adults benefit from 1,000 to 2,000 IU daily, though individual needs vary. Blood testing provides the clearest guidance. For bone health, levels between 30 and 50 ng/mL are commonly targeted, while levels below 20 ng/mL indicate deficiency.

Magnesium Supplements

Magnesium supports calcium balance and vitamin D activity. When dietary intake is low, supplementation can be helpful.

Forms with better absorption include magnesium citrate, magnesium glycinate, and magnesium malate. Magnesium oxide is poorly absorbed and is mainly used as a laxative.

Typical supplemental intake ranges from 200 to 400 mg daily, adjusted based on tolerance and dietary intake.

Vitamin K2 Supplements

Vitamin K2 supports calcium placement in bone tissue. Supplementation may be useful for people who rarely consume fermented foods or certain animal products.

The MK 7 form is preferred due to better absorption and longer activity in the body. Typical supplemental intake ranges from 90 to 180 mcg daily.

Anyone using blood-thinning medications such as warfarin should consult a healthcare provider before supplementing, as vitamin K affects clotting.

Omega-3 Supplements

Omega-3 fatty acids support bone health by helping regulate inflammation. Supplements are most useful when fatty fish is not consumed regularly.

Fish oil provides EPA and DHA directly. Algae oil offers a vegan alternative with the same active forms. Krill oil is another option, though often more expensive.

Most supplemental regimens provide between 1,000 and 2,000 mg of combined EPA and DHA daily. Product quality matters, so third-party testing for purity and contaminants is important.

Combination Bone Health Supplements

Some products combine calcium, vitamin D, magnesium, and other nutrients into a single formula. These can be convenient, but labels require careful review.

Look for clearly stated elemental calcium content, adequate vitamin D dosage, well-absorbed mineral forms, and minimal fillers. Independent testing from organizations such as USP, NSF, or ConsumerLab adds an extra layer of assurance.

Meal Planning Made Simple

Meeting bone health nutrition targets does not require perfect tracking or rigid meal plans. The goal is consistency across the day, using familiar foods in repeatable combinations.

Daily Bone Health Targets

Once you understand these targets, meal planning becomes pattern-based rather than prescriptive.

Examples of a Good Diet for Osteoporosis

Sample Day: Dairy Based

Breakfast

Greek yogurt with berries, ground flaxseed, and sliced almonds.

Whole grain toast with almond butter.

Lunch

Spinach salad with grilled salmon, cherry tomatoes, cucumber, and feta.

Olive oil and lemon dressing with a whole grain roll.

Dinner

Stir-fried calcium-set tofu with bok choy, broccoli, and snap peas.

Brown rice with sesame seeds.

Snack

String cheese and an apple.

Daily snapshot

Calcium and protein targets met. Vitamin D intake is close to goal. Omega-3 intake exceeds minimums.

Sample Day: Dairy Free

Breakfast

Oatmeal made with fortified soy milk, topped with chia seeds, walnuts, and banana.

Calcium-fortified orange juice.

Lunch

Lentil soup made with bone broth.

Kale salad with tahini, chickpeas, and shredded carrots.

Whole grain crackers.

Dinner

Baked chicken breast with roasted sweet potato and steamed collard greens.

Sauerkraut on the side.

Snack

Fortified almond milk smoothie with spinach, banana, and almond butter.

Daily snapshot

Calcium and protein targets met. Vitamin D intake improved with fortified foods, though supplementation would help reach optimal range.

Flexible Meal Building Ideas

Instead of fixed recipes, focus on combinations that repeat well.

Breakfast foundations

✓ Eggs with greens and cheese

✓ Yogurt or plant-based yogurt with nuts and seeds

✓ Smoothies with fortified milk and nut butter

Lunch and dinner anchors

✓ Fatty fish with vegetables and grains

✓ Chicken or tofu with leafy greens and legumes

✓ Soups or stews built on bone broth

Simple snacks

✓ Greek yogurt with almonds

✓ Cheese with whole grain crackers

✓ Edamame

✓ Hard-boiled eggs

✓ Nut butter with fruit

Make It Easier During the Week

A small amount of prep reduces daily decision-making.

Batch cooking bone broth, hard-boiled eggs, cooked beans or lentils, and roasted or grilled fish creates mix-and-match options. Keeping washed greens and chopped vegetables ready makes balanced meals faster.

A simple shopping rhythm helps reinforce consistency:

- Dairy or fortified alternatives

- Protein sources for several days

- Dark leafy greens and vegetables

- Pantry staples like canned fish, nuts, seeds, and whole grains

In practice, a good diet for osteoporosis is less about perfect tracking and more about meeting core nutrient needs consistently.

Nutrition and Vibration Therapy Together

Nutrition supplies the building materials bones need, but bone tissue also responds to physical signals. Without mechanical stimulation, nutrients alone may not fully support bone maintenance or adaptation.

Low-intensity vibration therapy provides that missing signal. While diet delivers calcium, protein, and supporting nutrients, vibration stimulates bone-forming cells and supports circulation, balance, and muscle engagement. Addressing both inputs supports bone tissue more effectively than either approach on its own.

Research on combined strategies suggests that pairing adequate nutrition with mechanical stimulation leads to better bone density outcomes than nutrition alone, particularly in postmenopausal women.

In practice, this combination is simple. Nutrition changes work gradually over time. Vibration therapy is typically used for short daily sessions. Using a device such as Marodyne LiV alongside regular meals or supplement routines makes consistency easier.

The goal is regular exposure to both the nutrients bones need and the signals that encourage bones to use them.

A Practical Approach to Bone-Healthy Nutrition

Bone health is supported by what you do consistently, not by perfection or short-term changes. A practical approach focuses on meeting core nutrient needs through everyday foods, spreading intake across the day, and adjusting as needed based on age, health status, and lifestyle.

Most people can meet these needs with familiar foods. Dairy or fortified alternatives, leafy greens, fatty fish, nuts, seeds, beans, and lean proteins form a reliable foundation. Supplements are useful when gaps exist, particularly for vitamin D or calcium, but they work best as support rather than substitutes for food.

Nutrition does not work in isolation. Vitamin D status, physical activity, and mechanical stimulation all influence how bone tissue responds over time. Addressing these factors together supports long-term maintenance more effectively than focusing on any single element.

A good diet for osteoporosis supports bone health most effectively when it is realistic, consistent, and adapted over time. The goal is sustainability. When nutrition habits are realistic and repeatable, they are more likely to support bone health over the long run.

Black Friday → Christmas Sale! Save $300 + Free Shipping

Black Friday → Christmas Sale! Save $300 + Free Shipping